How do Bulletproofs avoid the trusted setup phase?

Published:

When you are just entering into the ZKP realm, digging into zk-SNARKs protocols such as Groth16, Plonk, Bulletproofs, etc, you may pose yourself questions as follows:

1) What is the trusted setup protocol? 2) What is universal trusted setup vs circuit-specific setup? 3) Why other ZKP protocols such as zk-STARK or Bulletproofs don't require a trusted setup phase? Otherwise, why Groth16 and Plonk-KZG protocols require a trusted setup phase?

In many zero-knowledge proof systems, particularly zk-SNARKs (Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Arguments of Knowledge), a trusted setup phase is necessary. During this phase, certain cryptographic parameters (often referred to as a Common Reference String or CRS) are generated. These parameters are crucial for the functioning of the proof system, and their security must be ensured because anyone who knows the secret values used to generate these parameters could potentially create fraudulent proofs.

In the post “What happened in the trusted setup phase of the Groth16 protocol?”, I provided insights for the first two questions. In this post, I will try to explain why Bulletproofs protocol can work without the trusted setup and its differences from Groth16 and Plonk-KZG zk-SNARKs.

A brief recall of zk-SNARKs

To have complete knowledge of ZKP and zk-SNARKs, I would recommend you watch the ZKP MOOC Lectures). Personally, I see that lecture 2 Overview of Modern SNARK construction and lecture 5 The Plonk SNARK provided a great introduction to modern zk-SNARKs. Another excellent resource for understanding the Groth16 protocol is Rareskills’ ZK book (I implemented Python lectures of this book in this repo). This section will briefly summarize what I got from those lectures about zk_SNARKs.

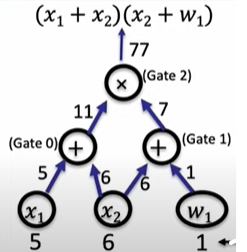

Give a correctness of computation problem. Let’s say, there is a complex problem in which you know its solution, for example, you know the shortest paths connecting all vertices in a very large graph, and you want to prove the someone that your solution is correct without reavealing the actual solution. So, you need to build a ZK proof for your statement. To do so, you first transform it into an arithmetic circuit consisting of multiplication and addition gates as shown in the below picture (source: ZKP MOOC Lecture 5).

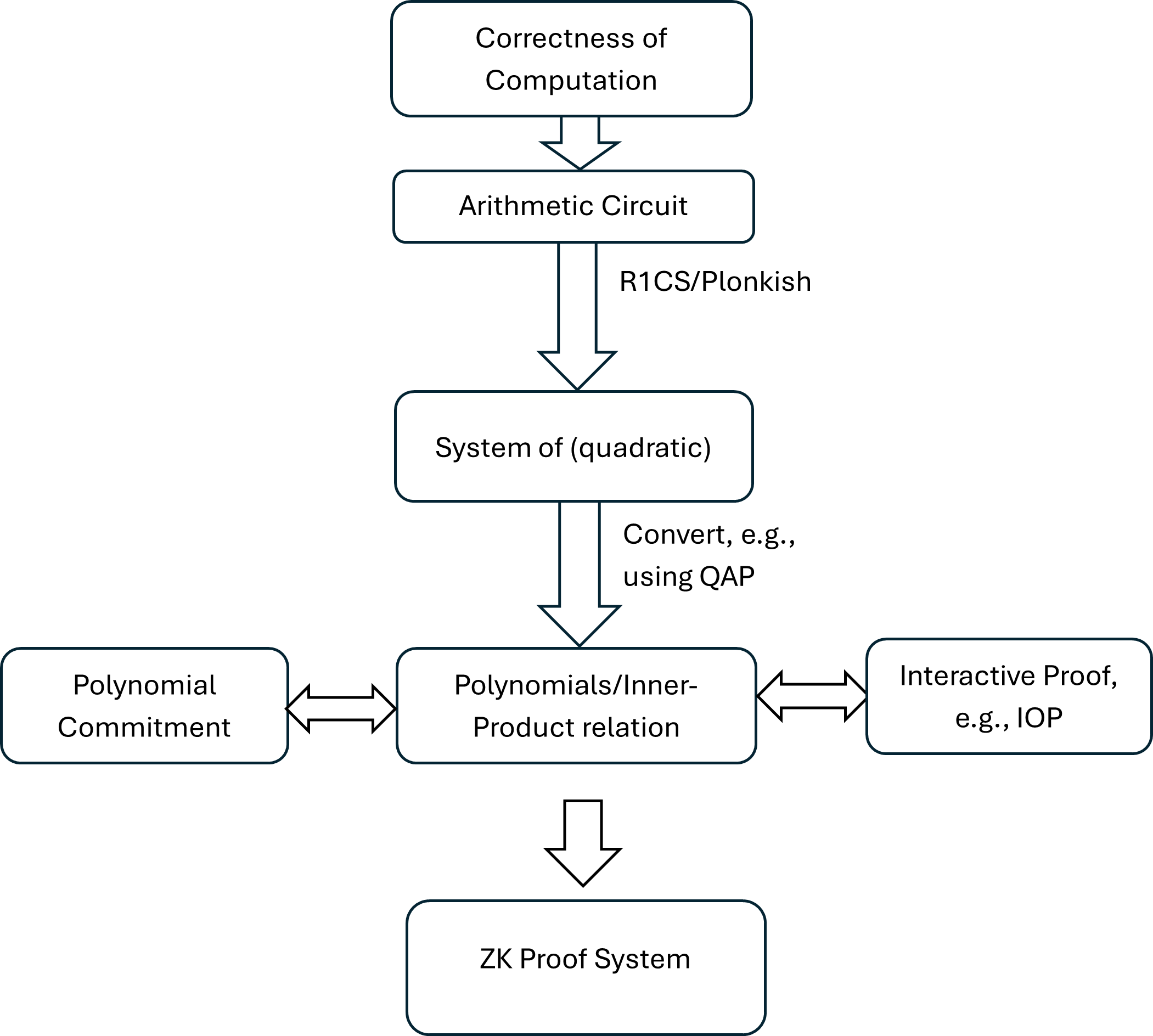

Then, using an arithmetization, you will convert those circuits to a set of mathematical equations, a.k.a., constraint system. If you have been in the field long enough, you might be familiar with terms like R1CS (Rank-1 Constraint System), and Plonkish arithmetization, two different methods you can express algebraic circuits. In the next step, a tool such as QAP (Quadratic Arithmetic Program) will help you to transform that set of mathematical equations (or Hadamard Product) into polynomials. The reason why we use polynomials is that a big matrix of many values can be equivalently represented by a polynomial, that then can be encrypted as a group element. Instead of committing your computation to a proof system, you just need to commit those polynomials. Which polynomial commitment scheme you use, is probably the most important factor in deciding the efficiency of your ZKP system.

Based on underlying cryptographic primitives, modern polynomial commitment schemes can be classified as follows:

- Pairing: KZG and Dory schemes

- Discrete-log: Bulletproofs, Hydrax

- Hash-function: zk-STARK

In this post, I introduced the KZG polynomial commitment scheme.

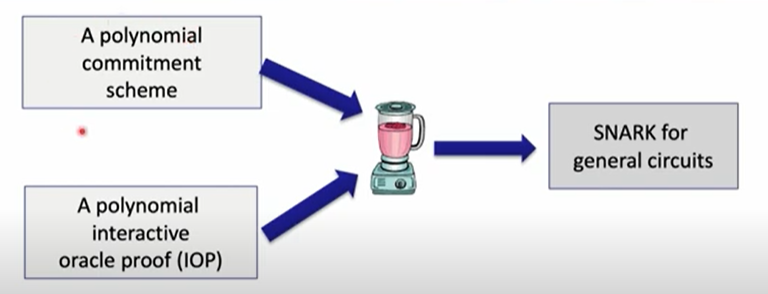

Finally, as mentioned in ZKP MOOC Lecture 2, any polynomial IOP combined with a polynomial commitment scheme can form a public coin interactive argument (see below picture, source: ZKP MOOC Lecture 5), which can be converted to a non-interactive ZKP or zk-SNARK via the well-known Fiat-Shamir transformation. Furthermore, a SNARK protocol requires the proof to be succinct and the verification should be much more quickly than the computation itself. For instance, The original Plonk ZKP is a combination of Plonk IOP and the KZG polynomial commitment. Halo 2 ZKP system combines Plonk IOP and Bulletproofs-based polynomial commitment.

From my understanding, I summarize in the below diagram processes that generate a ZK proof from a given correctness of computation problem.

What is Bulletproofs?

The Bulletproofs protocol was introduced by Benedikt Bünz, Jonathan Bootle, Dan Boneh, Andrew Poelstra, Pieter Wuille, and Greg Maxwell in their paper published in 2017. Unlike some other zk-SNARKs, Bulletproofs do not require a trusted setup, i.e., transparent setup. This means there is no need for a preliminary phase where a trusted party generates certain parameters that, if compromised, could undermine the security of the entire system. The absence of a trusted setup increases the security and trustworthiness of Bulletproofs.

Bulletproofs was originally known as a range proof protocol (proving that a value $v$ lies within a certain range without revealing the value itself, i.e., $0 \le v \le 2^n$), it was then adapted to an efficient zero-knowledge argument for arbitrary arithmetic circuits, a.k.a, any computations.

Bulletproofs protocol produces a proof of size $\mathcal{O}(log |C|)$ and verification time asymptotically requires $\mathcal{O}(|C|)$, where $C$ is the size of gates of the computation. These asymptotic complexities are actually pretty big compared to other zk-SNARKs protocols such as Groth16 or Plonk-KZG, in which those values are $\mathcal{O}(1)$.

How do Bulletproofs work?

Two important building blocks in the Bulletproofs protocol are Pedersen vector commitment and Inner Product Argument (IPA). Vitalik provided a very good high-level explanation of IPA in this post. I won’t recall details of these two cryptographic techniques here as many online resources are available if you Google them. Here I just briefly recall how they are used in the Bulletproofs to prove that a value $v$ belongs to a range $[0, 2^n - 1]$. I would refer readers to the paper Bulletproofs: Short Proofs for Confidential Transactions and More for the detailed technical description.

Inner-Product Argument

Given two vectors $\mathbf{a}, \mathbf{b} \in \mathbb{Z}_p^n$ of size $n$. Bulletproofs introduced an efficient algorithm to calculate an IPA for the below relation:

\[(\mathbf{g}, \mathbf{h} \in \mathbb{G}^n, \,\; u, P \in \mathbb{G}, \;\; \mathbf{a}, \mathbf{b} \in \mathbb{Z}_p^n) : P = \mathbf{g}^{\mathbf{a}} \mathbf{h}^{\mathbf{b}} \cdot u^{\langle \mathbf{a}, \mathbf{b} \rangle}\]The trivial way is to send $2n$ elements to the verifier, however this is not succinct when the size of vectors $n$ is growing. The Pedesen vector commitment scheme allows a vector to be cut in half and then to combine two halves together. A recursive process will be applied to reduce a proof from size of $n$ into $\log_2(n)$. That works as follows. Let $n’ = n/2$, and $H : \mathbb{Z}_p^{2n + 1} \rightarrow \mathbb{G}$ be a hash function, that takes as inputs $\mathbf{a}, \mathbf{a’}, \mathbf{b}, \mathbf{b’} \in \mathbb{Z}_p^{n’}$ and $c \in \mathbb{Z}_p$ and output:

\[H(\mathbf{a}, \mathbf{a'}, \mathbf{b}, \mathbf{b'}, c) = \mathbf{g}_{[:n']}^{\mathbf{a}} \cdot \mathbf{g}_{[n':]}^{\mathbf{a'}} \cdot \mathbf{h}_{[:n']}^{\mathbf{b}} \cdot \mathbf{h}_{[n':]}^{\mathbf{b'}} \cdot u^c \;\;\; \in \mathbb{G}\]By defining that, \(P = H(\mathbf{a}_{[:n']}, \mathbf{a}_{[n':]}, \mathbf{b}_{[:n']}, \mathbf{b}_{[n':]}, \langle \mathbf{a}, \mathbf{b} \rangle) \;\;\; \in \mathbb{G}\)

The prover calculates: \(L = H(\mathbf{0}^{n'}, \mathbf{a}_{[:n']}, \mathbf{b}_{[n':]}, \mathbf{0}^{n'} \langle \mathbf{a}_{[:n']}, \mathbf{b}_{[n':]} \rangle) \;\;\; \in \mathbb{G}\)

\[R = H(\mathbf{a}_{[n':]}, \mathbf{0}^{n'}, \mathbf{0}^{n'}, \mathbf{b}_{[:n']} \langle \mathbf{a}_{[n':]}, \mathbf{b}_{[:n']} \rangle) \;\;\; \in \mathbb{G}\]The first round of recursion works as folows:

- The prover sends $L, R$ to verifier

- The verifier chooses a random $x \leftarrow \mathbb{Z}_p$ and send it to the prover.

- The prover calculates $\mathbf{a’}, \mathbf{b’}$, then sends them to verifier, where: \(\mathbf{a'} = x\mathbf{a}_{[:n']} + x^{-1}\mathbf{a}_{[n':]} \in \mathbb{Z}_p^{n'}\) \(\mathbf{b'} = x^{-1}\mathbf{b}_{[:n']} + x\mathbf{a}_{[n':]} \in \mathbb{Z}_p^{n'},\)

- Given $(L, R, \mathbf{a’}, \mathbf{b’})$, the verifier computes $P’ = L^{x^2} \cdot P \cdot R^{x^{-2}}$ and outputs accept if:

After just one round, we can see that the elements sent to verifier reduces from $2n$ to $n + 2$, i.e., the tuple $(L, R, \mathbf{a’}, \mathbf{b’})$, approximately cut in half. Opening the commitment $P$ is now equivalent to opening $P’ = (\mathbf{g}{[:n’]}^{x^{-1}} \circ \mathbf{g}{[n’:]}^x)^{\mathbf{a’}} \cdot (\mathbf{h}{[:n’]}^{x} \circ \mathbf{h}^{x^{-1}}{[n’:]})^{\mathbf{b’}} \cdot u^{\langle \mathbf{a’}, \mathbf{b’} \rangle}$, where $\circ$ is wise-elements product.

If we repeatedly this process $n$ rounds, the final proof will be $2\lceil \log_2(n)\rceil$ elements in $\mathbb{G}$ and $2$ elements in $\mathbb{Z}_p$, that is:

\[(L_1, R_1), \ldots, (L_{\log_2 n}, R_{\log_2 n}) \in \mathbb{G}^2, \;\; a, b \in \mathbb{Z}^2\]Last but not least, the above interactive protocol can be transformed into a non-interactive protocol by applying Fiat-Shamir heuristic.

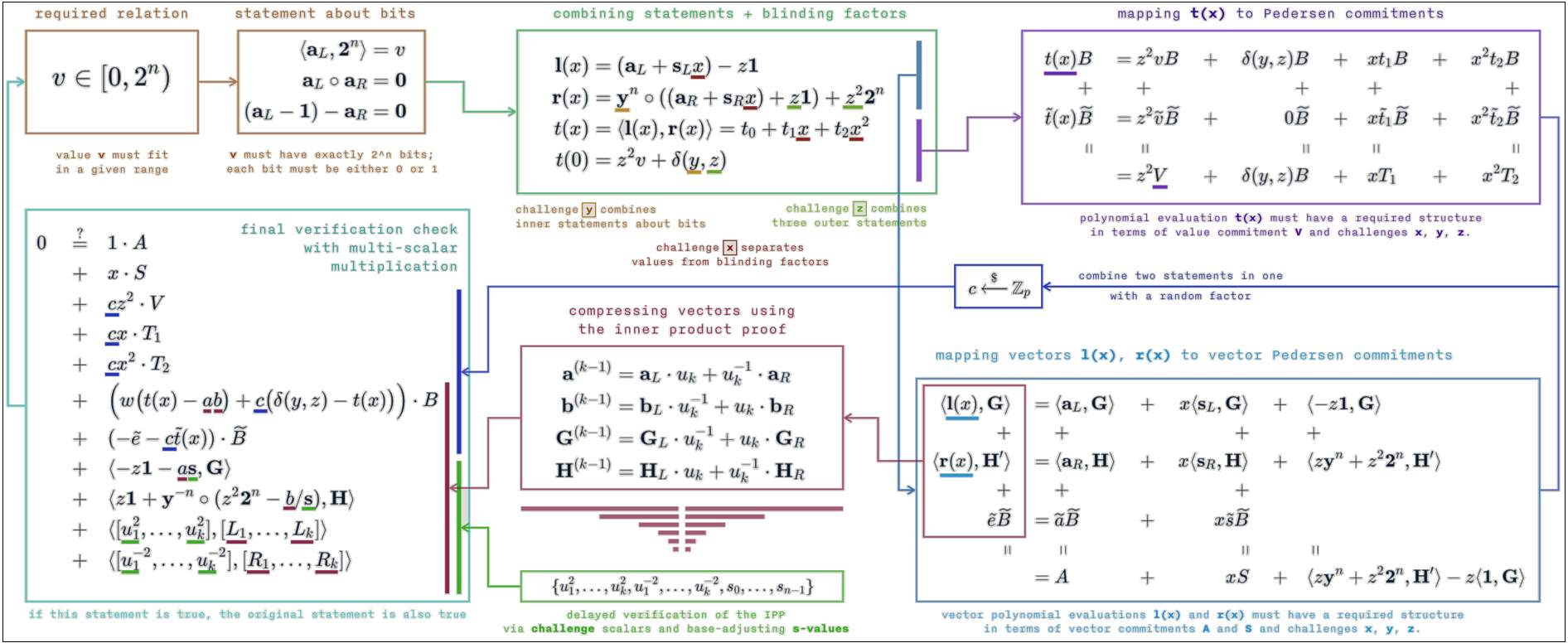

Inner-Product Range Proof

Assume that we are proving a value $v \in \mathbb{Z}_p$. Let $\mathbf{a}_L = (a_1, \ldots, a_n) \in {0, 1}^n$ be the vector containing the bits of $v$, so that the inner-product relation $\langle \mathbf{a}_L, \mathbf{2}^n \rangle = v$ holds, where vector $\mathbf{2}^n = (1, 2, \ldots, 2^{n - 1})$. Proving $v$ in range $[0, 2^2 -1]$ is equivalent to proving:

\[\langle \mathbf{a}_L, \mathbf{2}^n \rangle = v \quad \text{ and } \quad \mathbf{a}_R = \mathbf{a}_L - \mathbf{1}^n \quad \text{ and } \quad \mathbf{a}_L \circ \mathbf{a}_R = \mathbf{0}^n\]The above relation prove that the vector $\mathbf{a}_L$ is made of bits of $v$ and its values are either $0$ or $1$. By further applying algebraic transformations, this relation is reduced to a single inner-product argument. The below diagram visualizing the entire process provided by Interstellar.

Why Bulletproofs don’t require trusted setup?

The entire Bulletproofs protocol as described above does not apply to any secret information that requires a trusted setup phase like in Groth16 or Plonk-KGZ ZKP protocols. By using Pedersen vector commitment and Inner-Product Argument, the security of Bulletproofs protocol relies only on a standard cryptographic assumption, i.e., the hardness of discrete logarithms rather than on any secret setup parameters. All parameters used in Bulletproofs, including two vectors of group elements $\mathbf{g}$, and $\mathbf{h}$ are publicly verifiable and do not require secrecy.

Bulletproofs for arbitrary arithmetic circuits

We will discuss in the following how Bulletproofs are used to generate a general ZK circuit rather than a range proof. There are two approaches:

- either using

R1CSarithmetizationThis approach was implemented byInterstellarfor the next generation of Chain’s Confidential Assets. - or using

Plonkisharthmetization. This approach was realized in Halo 2.

For the first approach, as we know a computation will be represented by an arithmetic circuit, then converted into a R1CS system (i.e., Hadamard Product relation). Groth16 protocol applies Quadratic Arithmetic Program to convert a Hadamard Product relation to an equation of polynomials, then these polynomials are encrypted to elliptic curve points and finally the relation is verified by using a cryptographic pairing.

This repo provides a Pythom implementation for Groth16.

Different from Groth16, Bulletproofs-based ZKP system converts a Hadamard Product relation to a single inner product relation, that then will be prove by applying IPA and Pedersen vecter commitment as the original Bulletproofs protocol for range proof.

For the second approach, as mentioned earlier, if Bulletproofs could be used as a polynomial commitment, then it can be combined with a polynomial IOP such as Plonk to form a modern SNARK system. Let’s see how can we use Bulletproofs protocol to commit a polynomial.

Assume we need to commit a polynomial $f(X) = f_0 + f_1 x + \cdots + f_d x^d \in \mathbb{Z}_p(X)$. The Bulletproofs-based commitment is $com_f = g_0^{f_0} g_1^{f_1} \cdots g_d^{f_d}$, a form of Pedersen vector commitment, where $g_i \in \mathbb{G}$ for $i = 1, \ldots, d$. In a short term, $com_f$ can be rewritten as $com_f = \mathbf{g}^{\mathbf{f}}$, where $\mathbf{g} = (g_0, g_1, …, g_d)$, and $\mathbf{f} = (f_0, f_1, …, f_d)$ are two vectors of group elements of $\mathbb{G}$ and elements in finite field $\mathbb{Z}_p$, respectively.

The below table compares how a polynomial will be committed using KZG and Bulletproofs protocols.

| KZG poly-commitment | Bulletproof poly-commitment | |

|---|---|---|

$\mathbb{G}_1,\mathbb{G}_2$ groups of EC points (same pairing-friendly ellitpic curve shape, but in defined in two different finite fields) | $\mathbb{G}$ group of points of a (more generic) elliptic curve | |

| Setup | $g_1, g_2$, corresponding generators of $\mathbb{G}_1,\mathbb{G}_2$ | $g_0, g_1, \ldots, g_d \in \mathbb{G}$, arbitrary EC points |

$e$, a cryptographic pairing, and $\tau \in \mathbb{Z}_p$, a secret or toxic waste | ||

| CRS | $g_1, g_1^{\tau}, \ldots, g_1^{\tau^d}$, and $g_2^{\tau}$ | $g_i$ for $i \in [0, d]$ |

| Commitment | $com_f = g_1^{f(\tau)}$ | $com_f = \mathbf{g}^{\mathbf{f}}$ |

| Evaluation | $f(x) - f(u) = (x -u)q(x)$ | Apply IPA to reduce the size of $f$ in half |

| Proof | $\pi = g_1^{q(\tau)}$ | $L, R, v_L, v_R$ |

| Verification | $e(com_f/g_1^{f(u)}, g_2) = e(\pi, g_2^{\tau}/g_2^{u})$ | $v = v_L + v_R u^{d/2}$, $com_{f_{i+1}} = L_i^{r_i^2} \cdot com_{f_i} \cdot R_i^{r_i^{-2}} $ |

More technical details of Bulletproofs-based polynomial commitment could be found in this video lecture.

KZG poly-commitment proves that you know $f(x)$ and $q(x)$ such that the relation $q(x) = \frac{f(x) - f(u)}{(x - u)}$ holds. The remainder of $\frac{f(x) - f(u)}{(x - u)}$ should be $0$ as $u$ is a root of the polynomial $f(X) - f(u)$. Verifying this relation requires polynomials $f(x)$ and $q(x)$ to be evaluated in their correct forms, thus there is a need of a secret value $\tau$ and its powers to be setup in a trusted phase. In the other hand, Bulletproofs-based polynomial commitment relies Pedersen vector commitment and Inner-Product Argument and does not require any secret setup parameters as its range proof version.